A vast reservoir of the potent greenhouse gas methane may be locked beneath the Antarctic ice sheet, a study suggests.

Scientists say the gas could be released into the atmosphere if enough of the ice melts away, adding to global warming.

Research indicates that ancient deposits of organic matter may have been converted to methane by microbes living in low-oxygen conditions.

The organic material dates back to a period 35m years ago when the Antarctic was much warmer than it is today and teeming with life.

Study co-author Prof Slawek Tulaczyk, from the University of California at Santa Barbara, said: "Some of the organic material produced by this life became trapped in sediments, which then were cut off from the rest of the world when the ice sheet grew. Our modelling shows that over millions of years, microbes may have turned this old organic carbon into methane."

Half the West Antarctic ice sheet and a quarter of the East Antarctic sheet lie on pre-glacial sedimentary basins containing around 21,000bn tonnes of carbon, said the scientists, writing in the journal Nature.

British co-author Prof Jemma Wadham, from the University of Bristol, said: "This is an immense amount of organic carbon, more than 10 times the size of carbon stocks in northern permafrost regions.

"Our laboratory experiments tell us that these sub-ice environments are also biologically active, meaning that this organic carbon is probably being metabolised into carbon dioxide and methane gas by microbes."

The amount of frozen and free methane gas beneath the ice sheets could amount to 4bn tonnes, the researchers estimate.

Disappearing ice could free enough of the gas to have an impact on future global climate change, they believe. More

This blog contains articles and commentary on Climate Change / Global Warming. These changes will have an affect on the entire planet and all of us who reside therein. Life as we know it will change drastically. There is also the view that there is a high likelihood of climate change being a precursor of conflits triggered by resource shortges.

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet responses to past climate warming

During ice-age glacial maxima of the last ~2.6 million years, ice sheets covered large portions of the Northern Hemisphere. Records from the retreat of these ice sheets during deglaciations provide important insights into how ice sheets behave under a warming climate.

During the last two deglaciations, the southernmost margins of land-based Northern Hemisphere ice sheets responded nearly instantaneously to warming caused by increased summertime solar energy reaching the Earth. Land-based ice sheets subsequently retreated at a rate commensurate with deglacial climate warming. By contrast, marine-based ice sheets experienced a delayed onset of retreat relative to warming from increased summertime solar energy, with retreat characterized by periods of rapid collapse.

Both observations raise concern over the response of Earth’s remaining ice sheets to carbon-dioxide-induced global warming. The almost immediate reaction of land-based ice margins to past small increases in summertime energy implies that the Greenland Ice Sheet could be poised to respond to continuing climate change. Furthermore, the prehistoric precedent of marine-based ice sheets undergoing abrupt collapses raises the potential for a less predictable response of the marine-based West Antarctic Ice Sheet to future climate change. More - PDF

During the last two deglaciations, the southernmost margins of land-based Northern Hemisphere ice sheets responded nearly instantaneously to warming caused by increased summertime solar energy reaching the Earth. Land-based ice sheets subsequently retreated at a rate commensurate with deglacial climate warming. By contrast, marine-based ice sheets experienced a delayed onset of retreat relative to warming from increased summertime solar energy, with retreat characterized by periods of rapid collapse.

Both observations raise concern over the response of Earth’s remaining ice sheets to carbon-dioxide-induced global warming. The almost immediate reaction of land-based ice margins to past small increases in summertime energy implies that the Greenland Ice Sheet could be poised to respond to continuing climate change. Furthermore, the prehistoric precedent of marine-based ice sheets undergoing abrupt collapses raises the potential for a less predictable response of the marine-based West Antarctic Ice Sheet to future climate change. More - PDF

Monday, August 27, 2012

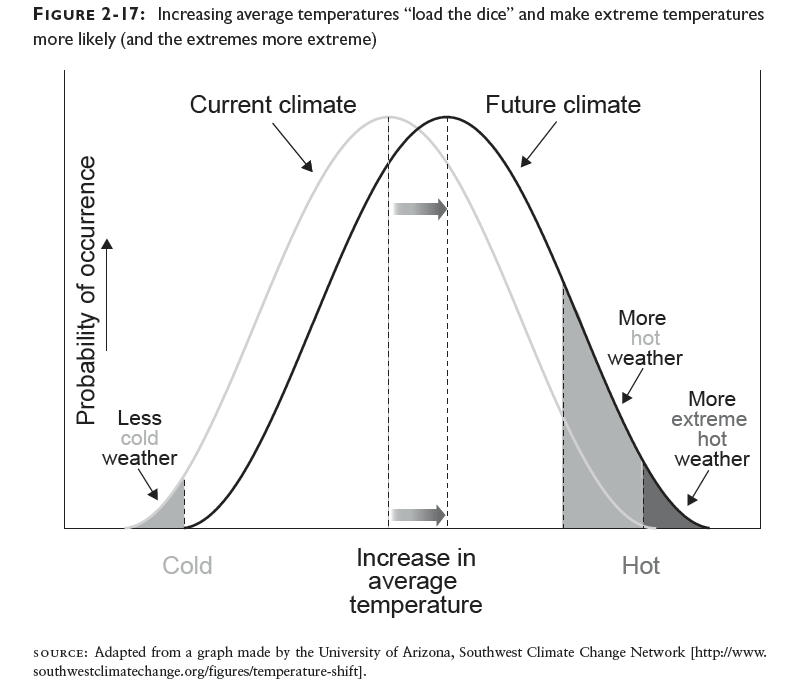

Why climate change causes BIG increases in extreme weather

Jim Hansen just published a terrific summary of the past few decades of temperature measurements, and it shows the stark reality: increasing the average temperature even a modest amount substantially increases the chances of extreme temperature events.

I showed this result conceptually in Figure 2-17 of Cold Cash, Cool Climate using a graph from the University of Arizona’s Southwest Climate Change Network:

Now, Hansen has calculated the actual distributions by decade to show what’s really been happening, and the results are striking. The overall summary is in his Figure 2:

Figure 2. Temperature anomaly distribution: The frequency of occurrence (vertical axis) of local temperature anomalies (relative to 1951-1980 mean) in units of local standard deviation (horizontal axis). Area under each curve is unity. Image credit: NASA/GISS. JK note added Aug. 14, 2012: the horizontal axis is NOT in units of temperature but in terms of standard deviations from the mean. For a normal distribution, which these graphs appear to be, about 68% of all the occurrences would be found within one standard deviation from the mean, and 95% of them would be within two standard deviations. When I figure out how to convert these results to temperature I’ll post again. More

I showed this result conceptually in Figure 2-17 of Cold Cash, Cool Climate using a graph from the University of Arizona’s Southwest Climate Change Network:

Now, Hansen has calculated the actual distributions by decade to show what’s really been happening, and the results are striking. The overall summary is in his Figure 2:

Figure 2. Temperature anomaly distribution: The frequency of occurrence (vertical axis) of local temperature anomalies (relative to 1951-1980 mean) in units of local standard deviation (horizontal axis). Area under each curve is unity. Image credit: NASA/GISS. JK note added Aug. 14, 2012: the horizontal axis is NOT in units of temperature but in terms of standard deviations from the mean. For a normal distribution, which these graphs appear to be, about 68% of all the occurrences would be found within one standard deviation from the mean, and 95% of them would be within two standard deviations. When I figure out how to convert these results to temperature I’ll post again. More

Labels:

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

extreme weather,

james hansen

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Building Resilience In A Changing Climate - Richard Heinberg

Climate shocks are on the way. We’ve already spewed so much carbon into the atmosphere that a cascade of worsening crop failures, droughts, floods, and freak storms is virtually guaranteed. You, your family, and your community will feel the effects.

Ironically, however, avoiding climate change also has its costs. It makes sense from a climate-protection standpoint to dramatically and rapidly reduce our use of fossil fuels, which drive global warming. But these fuels largely, well, fueled the spectacular economic growth of the past 200 years, and weaning ourselves from them quickly now—while most industrial economies are over-indebted and starved for growth—could risk financial upheaval.

Oil, the most economically pivotal of the fossil fuels, is getting more expensive anyway. Cheap, onshore, conventional crude is depleting; its replacements—deepwater oil, tar sands, and tight oil—cost more to produce, in both dollar and environmental terms. Though high oil prices discourage driving (good for the climate), they also precipitate recessions (bad for the economy). While renewable energy sources are our hope for the future and we should be doing everything we can to develop them, it will be decades before they can supply all our energy needs.

In the face of impending environmental and economic shocks, our best strategy is to build resilience throughout society. Resilience is the subject of decades of research by ecologists and social scientists who define it as “the capacity of a system to tolerate disturbance without collapsing into a qualitatively different state that is controlled by a different set of processes.” In other words, resilience is the capacity to absorb shocks, reorganize, and continue functioning.

In many respects a resilient society defies the imperative of economic efficiency. Resilience needs dispersed inventories and redundancy, while economic efficiency—in its ruthless pursuit of competitive advantage—eliminates inventories and redundancies everywhere it can. Economic efficiency leads toward globalization, resilience toward localization. Economic efficiency pursues short-term profit as its highest objective, while resilience targets long-term sustainability. It would appear that industrial society circa 2012 has gone about as far in the direction of economic efficiency as it is possible to go, and that a correction is necessary and inevitable. Climate change simply underscores the need for that course correction.

Building resilience means helping society to work more like an ecosystem—and that has major implications for how we use energy. Ecosystems conserve energy by closing nutrient loops: plants capture and chemically store solar energy, which is then circulated as food throughout the food web. Nothing is wasted. We humans—having developed the ability to draw upon ancient, concentrated, cheap, and abundant (though ultimately finite) fossil fuels—have simultaneously adopted the habit of wasting energy on a colossal scale. Our food, transport, manufacturing, and dwelling systems burn through thirty billion barrels of oil and eight billion tons of coal per year; globally, humans use over four hundred quadrillion BTUs of energy in total. Even where energy is not technically going to waste, demand for it could be substantially reduced by redesigning our basic systems. More

Ironically, however, avoiding climate change also has its costs. It makes sense from a climate-protection standpoint to dramatically and rapidly reduce our use of fossil fuels, which drive global warming. But these fuels largely, well, fueled the spectacular economic growth of the past 200 years, and weaning ourselves from them quickly now—while most industrial economies are over-indebted and starved for growth—could risk financial upheaval.

Oil, the most economically pivotal of the fossil fuels, is getting more expensive anyway. Cheap, onshore, conventional crude is depleting; its replacements—deepwater oil, tar sands, and tight oil—cost more to produce, in both dollar and environmental terms. Though high oil prices discourage driving (good for the climate), they also precipitate recessions (bad for the economy). While renewable energy sources are our hope for the future and we should be doing everything we can to develop them, it will be decades before they can supply all our energy needs.

In the face of impending environmental and economic shocks, our best strategy is to build resilience throughout society. Resilience is the subject of decades of research by ecologists and social scientists who define it as “the capacity of a system to tolerate disturbance without collapsing into a qualitatively different state that is controlled by a different set of processes.” In other words, resilience is the capacity to absorb shocks, reorganize, and continue functioning.

In many respects a resilient society defies the imperative of economic efficiency. Resilience needs dispersed inventories and redundancy, while economic efficiency—in its ruthless pursuit of competitive advantage—eliminates inventories and redundancies everywhere it can. Economic efficiency leads toward globalization, resilience toward localization. Economic efficiency pursues short-term profit as its highest objective, while resilience targets long-term sustainability. It would appear that industrial society circa 2012 has gone about as far in the direction of economic efficiency as it is possible to go, and that a correction is necessary and inevitable. Climate change simply underscores the need for that course correction.

Building resilience means helping society to work more like an ecosystem—and that has major implications for how we use energy. Ecosystems conserve energy by closing nutrient loops: plants capture and chemically store solar energy, which is then circulated as food throughout the food web. Nothing is wasted. We humans—having developed the ability to draw upon ancient, concentrated, cheap, and abundant (though ultimately finite) fossil fuels—have simultaneously adopted the habit of wasting energy on a colossal scale. Our food, transport, manufacturing, and dwelling systems burn through thirty billion barrels of oil and eight billion tons of coal per year; globally, humans use over four hundred quadrillion BTUs of energy in total. Even where energy is not technically going to waste, demand for it could be substantially reduced by redesigning our basic systems. More

Thursday, August 23, 2012

No-Till Could Help Maintain Crop Yields Despite Climate Change

ScienceDaily (Aug. 23, 2012) — Reducing tillage for some Central Great Plains crops could help conserve water and reduce losses caused by climate change, according to studies at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Research leader Laj Ahuja and others at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Agricultural Systems Research Unit at Fort Collins, Colo., superimposed climate projections onto 15 to 17 years of field data to see how future crop yields might be affected. ARS is USDA's chief intramural scientific research agency, and this work supports the USDA priority of responding to climate change.

The field data was collected at the ARS Central Great Plains Research Station in Akron, Colo. The projections included an increase in equivalent atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels from 380 parts per million by volume (ppmv) in 2005 to 550 ppmv in 2050. The projections also included a 5-degree Fahrenheit increase in summer temperatures in Colorado from 2005 to 2050. The ARS scientists used these projections to calculate a linear increase of CO2 and temperature from 2050 to 2100.

Ahuja's team used the Root Zone Water Quality Model (version 2) for crop rotations of wheat-fallow, wheat-corn-fallow, and wheat-corn-millet to see how yields might be affected in the future. They simulated different combinations of three climate change projections: rising CO2 levels, rising temperatures, and a shift in precipitation from late spring and sum¬mer to fall and winter. They ran the model with the projected climate for each of the 15 to 17 years of field crop data for each cropping system.

When the researchers used all three climate factors to generate yield projections from 2005 to 2100, the yield estimates for the three cropping systems dropped over time. Declines in corn and millet yields were more significant than declines in wheat yields. More

Research leader Laj Ahuja and others at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Agricultural Systems Research Unit at Fort Collins, Colo., superimposed climate projections onto 15 to 17 years of field data to see how future crop yields might be affected. ARS is USDA's chief intramural scientific research agency, and this work supports the USDA priority of responding to climate change.

The field data was collected at the ARS Central Great Plains Research Station in Akron, Colo. The projections included an increase in equivalent atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels from 380 parts per million by volume (ppmv) in 2005 to 550 ppmv in 2050. The projections also included a 5-degree Fahrenheit increase in summer temperatures in Colorado from 2005 to 2050. The ARS scientists used these projections to calculate a linear increase of CO2 and temperature from 2050 to 2100.

Ahuja's team used the Root Zone Water Quality Model (version 2) for crop rotations of wheat-fallow, wheat-corn-fallow, and wheat-corn-millet to see how yields might be affected in the future. They simulated different combinations of three climate change projections: rising CO2 levels, rising temperatures, and a shift in precipitation from late spring and sum¬mer to fall and winter. They ran the model with the projected climate for each of the 15 to 17 years of field crop data for each cropping system.

When the researchers used all three climate factors to generate yield projections from 2005 to 2100, the yield estimates for the three cropping systems dropped over time. Declines in corn and millet yields were more significant than declines in wheat yields. More

Labels:

agriculture,

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

drought,

Food,

food security,

United States

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Global Warming: Nobel Prize-Winner Mario Molina Links Recent Extreme Weather With Man-Made Climate Change

It’s highly likely that recent extreme weather events around the world were the result of man-made global warming, according to Nobel Prize-winning scientist Mario Molina.

Molina, who shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his part in the discovery that CFCs were depleting the ozone layer, said that extreme weather events were now strongly linked with man-made global warming.

Speaking at a meeting of the American Chemical Society, he said: “People may not be aware that important changes have occurred in the scientific understanding of the extreme weather events that are in the headlines.

"They are now more clearly connected to human activities, such as the release of carbon dioxide ― the main greenhouse gas ― from burning coal and other fossil fuels."

Molina, who lectures at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of California, emphasised that there is no "absolute certainty" that global warming is causing extreme weather events.

But he said that scientific insights during the last year or so strengthen the link. Even if the scientific evidence continues to fall short of the absolute certainty measure, the heat, drought, severe storms and other weather extremes may prove beneficial in making the public more aware of global warming and the need for action, said Molina.

"It's important that people are doing more than just hearing about global warming," he said. "People may be feeling it, experiencing the impact on food prices, getting a glimpse of what everyday life may be like in the future, unless we as a society take action."

Molina said that it's not certain what will happen to the Earth if nothing is done to slow down or halt climate change.

"But there is no doubt that the risk is very large, and we could have some consequences that are very damaging, certainly for portions of society," he said. "It's not very likely, but there is some possibility that we would have catastrophes." More

Molina, who shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his part in the discovery that CFCs were depleting the ozone layer, said that extreme weather events were now strongly linked with man-made global warming.

Speaking at a meeting of the American Chemical Society, he said: “People may not be aware that important changes have occurred in the scientific understanding of the extreme weather events that are in the headlines.

"They are now more clearly connected to human activities, such as the release of carbon dioxide ― the main greenhouse gas ― from burning coal and other fossil fuels."

Molina, who lectures at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of California, emphasised that there is no "absolute certainty" that global warming is causing extreme weather events.

But he said that scientific insights during the last year or so strengthen the link. Even if the scientific evidence continues to fall short of the absolute certainty measure, the heat, drought, severe storms and other weather extremes may prove beneficial in making the public more aware of global warming and the need for action, said Molina.

"It's important that people are doing more than just hearing about global warming," he said. "People may be feeling it, experiencing the impact on food prices, getting a glimpse of what everyday life may be like in the future, unless we as a society take action."

Molina said that it's not certain what will happen to the Earth if nothing is done to slow down or halt climate change.

"But there is no doubt that the risk is very large, and we could have some consequences that are very damaging, certainly for portions of society," he said. "It's not very likely, but there is some possibility that we would have catastrophes." More

Labels:

agriculture,

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

CO2,

cyclones,

drought,

Ecocide,

eradicating,

extreme weather,

Food,

food security,

hurricanes,

sea level,

sea level rise,

security,

water

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Europe swelters in summer heat wave

Europe is basking in a mid-August heatwave as temperatures soar in parts of the continent, breaking records and prompting officials to issue heat alerts.

Germany experienced its hottest day of the year on Sunday as temperatures neared 40 C, according to local media.

Over the weekend, parts of the U.K. encountered temperatures higher than in much of the Caribbean, reaching 32 C, the Telegraph reported.

France’s ministry of health has issued a weather alert urging the public to remain on guard against possible health risks.

The country’s weather services forecasted temperatures in the mid to high 30 C in the coming days, according to French media.

The heat has also sparked a number of fires across the continent.

Forest fires ravaged the eastern Greek Aegean island of Chios for a fourth day on Tuesday. Wildfires also threatened areas of Bosnia where temperatures reached 40 C.

In 2003, Europe was hit with a severe heat wave that killed thousands of people. More

Germany experienced its hottest day of the year on Sunday as temperatures neared 40 C, according to local media.

Over the weekend, parts of the U.K. encountered temperatures higher than in much of the Caribbean, reaching 32 C, the Telegraph reported.

France’s ministry of health has issued a weather alert urging the public to remain on guard against possible health risks.

The country’s weather services forecasted temperatures in the mid to high 30 C in the coming days, according to French media.

The heat has also sparked a number of fires across the continent.

Forest fires ravaged the eastern Greek Aegean island of Chios for a fourth day on Tuesday. Wildfires also threatened areas of Bosnia where temperatures reached 40 C.

In 2003, Europe was hit with a severe heat wave that killed thousands of people. More

Labels:

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

heat,

temperature,

weather

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Snow in August? It's steamy now, but forecasters see a big winter coming

Last winter, big cities like New York and Philadelphia saved a lot of money because the Northeast had a snow drought. Not so this winter.

Yes, even while air conditioners are still running, meteorologists are beginning to focus on the long-term winter weather forecast. And, it looks as if the I-95-corridor cities from Washington to Boston will need to make sure the plows are gassed up and rock salt plentiful.

“I think the East Coast is going to have some battles with some big storms,” says Paul Pastelok, Accu-Weather’s lead long-term forecaster in State College, Pa.

However, Mr. Pastelok predicts the battles won’t start until January and then will extend into February. “November in the Northeast could be above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation, and December could be a transition month,” he says. “By January and February it’s going to get pretty cold.”

The cold will collide with moisture flowing up the East Coast, he says, resulting in some big snowstorms that could create travel problems, close school systems and create challenges for retailers.

“The good news is that the winter will be good for hats, gloves, scarves, rock salt, and the plowing industry,” says Scott Bernhardt, president of Planalytics, Inc. a business weather intelligence service in Berwyn, Pa. “It’s bad for store traffic, because other than urban areas it’s hard to get around, and restaurants also take a hit because people just don’t go out.” More

Yes, even while air conditioners are still running, meteorologists are beginning to focus on the long-term winter weather forecast. And, it looks as if the I-95-corridor cities from Washington to Boston will need to make sure the plows are gassed up and rock salt plentiful.

“I think the East Coast is going to have some battles with some big storms,” says Paul Pastelok, Accu-Weather’s lead long-term forecaster in State College, Pa.

However, Mr. Pastelok predicts the battles won’t start until January and then will extend into February. “November in the Northeast could be above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation, and December could be a transition month,” he says. “By January and February it’s going to get pretty cold.”

The cold will collide with moisture flowing up the East Coast, he says, resulting in some big snowstorms that could create travel problems, close school systems and create challenges for retailers.

“The good news is that the winter will be good for hats, gloves, scarves, rock salt, and the plowing industry,” says Scott Bernhardt, president of Planalytics, Inc. a business weather intelligence service in Berwyn, Pa. “It’s bad for store traffic, because other than urban areas it’s hard to get around, and restaurants also take a hit because people just don’t go out.” More

Labels:

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

forecast,

new york,

prediction,

snow,

storm,

United States,

washington,

weather

Monday, August 13, 2012

Rivers, wells run dry; fish die in heat

OTTUMWA, Iowa -- Under the widest-reaching drought since 1956, and torched by the hottest July on record dating from 1895, the United States has been under the kind of weather stress that climatologists say will be more common if the long-standing trend toward higher U.S. temperatures continues.

Most immediately affected are the nation's water sources.

The flow of the Mississippi River has slowed -- at times rivaling 40-year-lows -- allowing saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico to seep far up the river channel, threatening community water supplies at the river mouth.

In Iowa, about 58,000 fish died along a 42-mile stretch of the Des Moines River, according to state officials, and the cause of death appeared to be heat. Biologists measured the water at 97 degrees in multiple spots.

In 1895, the first year of such records for the nation, the average July temperature in the contiguous states was 72.1 degrees.

Since then, average temperatures have been rising, if slowly, according to U.S. records, climbing at the rate of 1.24 degrees per century.

This year, average temperatures spiked to 77.6 -- even above the long-term trends, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported last week.

At the same time that temperatures have spiked, setting records in places as far-flung as Lansing and Greenville, S.C., the country has been hit with a spreading drought.

In early August, 62 percent of the contiguous United States was under moderate to exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

The heat and drought feed on each other, worsening conditions, scientists said. When the ground is wet, the water absorbs the sun's heat and expends it in evaporation; when the earth is dry in a drought, the ground simply warms.

The rising temperatures and spreading drought this year are consistent with what can be expected with the warming of the climate, said Jake Crouch, a climate scientist with NOAA.

"Any given year in the future could be above or below that rising trend," he said. "But if the current trend continues, the chances of years like this become greater."

The Midwest is particularly vulnerable to large swings, according to federal scientists, in part because it is farther from the oceans, which help to moderate temperatures.

"There is a high degree of confidence in projections that future temperature increases will be greatest in the Arctic and in the middle of continents," according to the U.S. Global Change Research Program. More

Most immediately affected are the nation's water sources.

The flow of the Mississippi River has slowed -- at times rivaling 40-year-lows -- allowing saltwater from the Gulf of Mexico to seep far up the river channel, threatening community water supplies at the river mouth.

In Iowa, about 58,000 fish died along a 42-mile stretch of the Des Moines River, according to state officials, and the cause of death appeared to be heat. Biologists measured the water at 97 degrees in multiple spots.

Across Indiana, wells have run dry, and farther across the nation's middle, many communities have invoked water restrictions to protect shrinking supplies."I've never seen anything quite like it," Justin Pedretti, who owns a farm near the boat ramp in Bonaparte, Iowa, and first reported the fish kill.

In 1895, the first year of such records for the nation, the average July temperature in the contiguous states was 72.1 degrees.

Since then, average temperatures have been rising, if slowly, according to U.S. records, climbing at the rate of 1.24 degrees per century.

This year, average temperatures spiked to 77.6 -- even above the long-term trends, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported last week.

At the same time that temperatures have spiked, setting records in places as far-flung as Lansing and Greenville, S.C., the country has been hit with a spreading drought.

In early August, 62 percent of the contiguous United States was under moderate to exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

The heat and drought feed on each other, worsening conditions, scientists said. When the ground is wet, the water absorbs the sun's heat and expends it in evaporation; when the earth is dry in a drought, the ground simply warms.

The rising temperatures and spreading drought this year are consistent with what can be expected with the warming of the climate, said Jake Crouch, a climate scientist with NOAA.

"Any given year in the future could be above or below that rising trend," he said. "But if the current trend continues, the chances of years like this become greater."

The Midwest is particularly vulnerable to large swings, according to federal scientists, in part because it is farther from the oceans, which help to moderate temperatures.

"There is a high degree of confidence in projections that future temperature increases will be greatest in the Arctic and in the middle of continents," according to the U.S. Global Change Research Program. More

Labels:

agriculture,

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

drought,

Food,

food security,

sea level rise,

security,

temperature,

water

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Rate of arctic summer sea ice loss is 50% higher than predicted

Sea ice in the Arctic is disappearing at a far greater rate than previously expected, according to data from the first purpose-built satellite launched to study the thickness of the Earth's polar caps.

Preliminary results from the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2 probe indicate that 900 cubic kilometres of summer sea ice has disappeared from the Arctic ocean over the past year.

This rate of loss is 50% higher than most scenarios outlined by polar scientists and suggests that global warming, triggered by rising greenhouse gas emissions, is beginning to have a major impact on the region. In a few years the Arctic ocean could be free of ice in summer, triggering a rush to exploit its fish stocks, oil, minerals and sea routes.

"Preliminary analysis of our data indicates that the rate of loss of sea ice volume in summer in the Arctic may be far larger than we had previously suspected," said Dr Seymour Laxon, of the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at University College London (UCL), where CryoSat-2 data is being analysed. "Very soon we may experience the iconic moment when, one day in the summer, we look at satellite images and see no sea ice coverage in the Arctic, just open water." More

Preliminary results from the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2 probe indicate that 900 cubic kilometres of summer sea ice has disappeared from the Arctic ocean over the past year.

This rate of loss is 50% higher than most scenarios outlined by polar scientists and suggests that global warming, triggered by rising greenhouse gas emissions, is beginning to have a major impact on the region. In a few years the Arctic ocean could be free of ice in summer, triggering a rush to exploit its fish stocks, oil, minerals and sea routes.

Using instruments on earlier satellites, scientists could see that the area covered by summer sea ice in the Arctic has been dwindling rapidly. But the new measurements indicate that this ice has been thinning dramatically at the same time. For example, in regions north of Canada and Greenland, where ice thickness regularly stayed at around five to six metres in summer a decade ago, levels have dropped to one to three metres.New satellite images show polar ice coverage dwindling in extent and thickness

"Preliminary analysis of our data indicates that the rate of loss of sea ice volume in summer in the Arctic may be far larger than we had previously suspected," said Dr Seymour Laxon, of the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling at University College London (UCL), where CryoSat-2 data is being analysed. "Very soon we may experience the iconic moment when, one day in the summer, we look at satellite images and see no sea ice coverage in the Arctic, just open water." More

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

The nuclear approach to climate risk - Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

From desertification in China to glacier melt in Nepal to water scarcity in South Africa, climate change is beginning to make itself felt in the developing world. As developing countries search for ways to contain carbon emissions while also maximizing economic potential, a natural focus of attention is nuclear power. But nuclear energy presents its own dangers. Below, Wang Haibin of China, Anthony Turton of South Africa, and Hira Bahadur Thapa of Nepal answer this question: "Given nuclear energy's potential to slow global warming, do its benefits outweigh its risks, or do its risks outweigh its benefits for developing countries?"

In his first Roundtable essay, Anthony Turton presented a perceptive analysis of the linkages among water scarcity, electricity demands, and climate change in South Africa. He also outlined inspiring ideas about easing that country's water constraints by using nuclear energy in the desalination of seawater. It is my view, however, that while Turton's ideas may be sound for South Africa, they have limited applicability in many other places -- including China.

If nuclear energy is to be developed in a sustainable fashion, cost-benefit ratios must always be kept clearly in mind -- and in different locations, nuclear power can present starkly different cost-benefit ratios. In developing countries with constrained water supplies and less constrained electricity supplies, it may make sense to use nuclear energy to desalinate seawater (and even to pump it to remote locations). But in developing nations where the population suffers from an urgent shortage of electricity, the idea of consuming a great deal of power to produce fresh water would seem to lack a firm economic basis.

China, a country whose economy and electricity needs are both growing rapidly, currently operates 15 nuclear reactors. More than one of these plants is used for desalinating seawater, but only when, as is the case with the Hongyanhe facility in Liaoning province, desalination is unavoidable. The pressurized water reactors at the Hongyanhe facility require a great deal of fresh water to operate, and the local supply of fresh water is inadequate for this purpose. Therefore, the plant has been designed to desalinate over 10,000 cubic meters of seawater daily for its own operation.

Significantly, the desalination technology that the plant has adopted is reverse osmosis. The choice is significant because reverse osmosis consumes less energy per unit of fresh water produced than do other desalination methods, rendering the energy needs and economic costs of desalination acceptable to the plant's operators. But -- according to an interview I recently conducted with a senior economist at China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group, the plant's owner -- the company has no plans to desalinate more seawater than the Hongyanhe facility needs for its own operation.

The company's decisions regarding desalination reflect a trade-off between water demands and power demands; such trade-offs are common in the developing world, where many countries require more water, more electricity, or both. I believe that, in a world where 1.5 billion people lack access to electricity, it is power demands that, on the whole, are more acute than water demands. More

In his first Roundtable essay, Anthony Turton presented a perceptive analysis of the linkages among water scarcity, electricity demands, and climate change in South Africa. He also outlined inspiring ideas about easing that country's water constraints by using nuclear energy in the desalination of seawater. It is my view, however, that while Turton's ideas may be sound for South Africa, they have limited applicability in many other places -- including China.

If nuclear energy is to be developed in a sustainable fashion, cost-benefit ratios must always be kept clearly in mind -- and in different locations, nuclear power can present starkly different cost-benefit ratios. In developing countries with constrained water supplies and less constrained electricity supplies, it may make sense to use nuclear energy to desalinate seawater (and even to pump it to remote locations). But in developing nations where the population suffers from an urgent shortage of electricity, the idea of consuming a great deal of power to produce fresh water would seem to lack a firm economic basis.

China, a country whose economy and electricity needs are both growing rapidly, currently operates 15 nuclear reactors. More than one of these plants is used for desalinating seawater, but only when, as is the case with the Hongyanhe facility in Liaoning province, desalination is unavoidable. The pressurized water reactors at the Hongyanhe facility require a great deal of fresh water to operate, and the local supply of fresh water is inadequate for this purpose. Therefore, the plant has been designed to desalinate over 10,000 cubic meters of seawater daily for its own operation.

Significantly, the desalination technology that the plant has adopted is reverse osmosis. The choice is significant because reverse osmosis consumes less energy per unit of fresh water produced than do other desalination methods, rendering the energy needs and economic costs of desalination acceptable to the plant's operators. But -- according to an interview I recently conducted with a senior economist at China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group, the plant's owner -- the company has no plans to desalinate more seawater than the Hongyanhe facility needs for its own operation.

The company's decisions regarding desalination reflect a trade-off between water demands and power demands; such trade-offs are common in the developing world, where many countries require more water, more electricity, or both. I believe that, in a world where 1.5 billion people lack access to electricity, it is power demands that, on the whole, are more acute than water demands. More

Labels:

alternative,

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

energy,

Nuclear,

risk

Monday, August 6, 2012

IEA Bombshell: Global Warming May Lead To ‘Miami Beach In Boston’ Situation Unless Urgent Action Is Taken

The International Energy Agency was, until recently, a conservative and staid body. When I was at the U.S. Department of Energy in the 1990s, we ignored most IEA reports, because, like the vast majority of energy forecasters, they inevitably projected that the future would simply continue the trends of the recent past.

But now, of course, if we stay on current trends, we are going to utterly destroy a livable climate and ruin the lives of billions of people. Even so, attention must be paid when a major international body is so uncharacteristically blunt, when they actually lead their website with this bombshell headline from their own news release!

Anyone who follows the IEA or Climate Progress knows that they and many others have been issuing this warning for the last year or two (see “Yes, Deniers And Confusionists, The IEA And Others Warn Of Some 11°F Warming by 2100 If We Keep Listening To You“).

And because the world just keeps blithely dumping more and more carbon pollution into the air, the leadership of the IEA has been increasingly blunt. Their chief economist, Fatih Birol, said late last year that the world is on pace for 11°F warming, and “Even School Children Know This Will Have Catastrophic Implications for All of Us.” If only school children ran the world!

The IEA news release is about the recent remarks of Deputy Executive Director Richard H. Jones: More

But now, of course, if we stay on current trends, we are going to utterly destroy a livable climate and ruin the lives of billions of people. Even so, attention must be paid when a major international body is so uncharacteristically blunt, when they actually lead their website with this bombshell headline from their own news release!

Anyone who follows the IEA or Climate Progress knows that they and many others have been issuing this warning for the last year or two (see “Yes, Deniers And Confusionists, The IEA And Others Warn Of Some 11°F Warming by 2100 If We Keep Listening To You“).

And because the world just keeps blithely dumping more and more carbon pollution into the air, the leadership of the IEA has been increasingly blunt. Their chief economist, Fatih Birol, said late last year that the world is on pace for 11°F warming, and “Even School Children Know This Will Have Catastrophic Implications for All of Us.” If only school children ran the world!

The IEA news release is about the recent remarks of Deputy Executive Director Richard H. Jones: More

Labels:

change,

climate,

climate change,

climate smart,

sea level,

sea level rise

Saturday, August 4, 2012

Scientists Tell Senate Panel: Climate Change Is Here and Disaster Costs Will Be Huge

Climate scientists who appeared Wednesday morning before a Senate committee hearing on climate change and extreme weather impacts had stark warnings for the lawmakers: climate change is here, climate change is man-made, and climate change is going to cost us big time.

Dr. James McCarthy, professor at Harvard University and lead author of several climate impact studies by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other international papers, told the committee that there is "widespread agreement among specialists who devote their careers" to monitoring key indicators of global warming.

He acknowledged that, of course, climates fluctuate on a yearly basis, but that the mounting evidence of a warming world was changing the baseline of those fluctuations.

"In the future," he said, as greenhouse gases continue to increase, natural events like El Nino cycles, "Will wreak even more havoc as they break old records for warm and wet conditions across much of the globe, because they will be occurring upon a higher baseline of warming."

His IPCC colleague and climate scientist at Stanford University Dr. Christopher Fields, said that these events will have an increasingly strong impact on communities.

"Understanding the role of climate change in the risk of extremes is one of the most active areas of climate science," he said. "As a result of rapid progress over the last few years, it is now feasible to quantify the way that climate change alters the risk of certain events or series of events." More

|

| Senator Jim Ihhofe, Climate Skeptic |

He acknowledged that, of course, climates fluctuate on a yearly basis, but that the mounting evidence of a warming world was changing the baseline of those fluctuations.

"In the future," he said, as greenhouse gases continue to increase, natural events like El Nino cycles, "Will wreak even more havoc as they break old records for warm and wet conditions across much of the globe, because they will be occurring upon a higher baseline of warming."

His IPCC colleague and climate scientist at Stanford University Dr. Christopher Fields, said that these events will have an increasingly strong impact on communities.

"Understanding the role of climate change in the risk of extremes is one of the most active areas of climate science," he said. "As a result of rapid progress over the last few years, it is now feasible to quantify the way that climate change alters the risk of certain events or series of events." More

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Drought diaries: How no water, extreme heat are hurting Americans

Along the 195-mile Embarras River, a tributary of the Wabash in southeastern Illinois, rancher Jim Gardner worries about his 200 head of Angus cattle.

There's enough hay -- for now. But in July, the cattle started eating winter's food, and this year's drought has already browned his fields. When the rain stopped, the ranch cut the hay for feed. The fields are now barren.

"You have a choice: Spend money to buy hay or spend money on fuel to get hay. We may be looking for hay again in October," Gardner writes in a first-person piece for Yahoo News.

The Embarras flows north to south, meandering through seven Illinois counties that have all been designated as "extreme" drought by the federal government. Like more than 1,500 counties across the country, water along the river is sparse or non-existent.

"The ponds are gone. They're just big craters now. The trees are dropping leaves, diminishing what little shade they have," Gardner writes. "Dust billows up like a giant wave, rising through barren locust trees when the cows head to pasture."

He said that this May he improved two fields by spreading turkey manure on them -- and it worked, sort of. They were last fields to turn brown in the drought.

"For more than 100 years, someone from our family has worked this dry ground," he writes. "Every decision we make carries risk of failure of ending that tradition."

Gardner's story is one of undoubtedly thousands of drought-related anecdotes from across the United States. There's plenty of misery to spread around: On Wednesday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture named 218 additional counties to its tally of natural disaster areas, raising the number of counties nationwide with drought designations to 1,584 in 32 states. And -- as millions of Americans have learned this summer -- if it's not the drought that's problematic, it's the drought's ugly cousin: the heat wave. More

There's enough hay -- for now. But in July, the cattle started eating winter's food, and this year's drought has already browned his fields. When the rain stopped, the ranch cut the hay for feed. The fields are now barren.

"You have a choice: Spend money to buy hay or spend money on fuel to get hay. We may be looking for hay again in October," Gardner writes in a first-person piece for Yahoo News.

The Embarras flows north to south, meandering through seven Illinois counties that have all been designated as "extreme" drought by the federal government. Like more than 1,500 counties across the country, water along the river is sparse or non-existent.

"The ponds are gone. They're just big craters now. The trees are dropping leaves, diminishing what little shade they have," Gardner writes. "Dust billows up like a giant wave, rising through barren locust trees when the cows head to pasture."

He said that this May he improved two fields by spreading turkey manure on them -- and it worked, sort of. They were last fields to turn brown in the drought.

"For more than 100 years, someone from our family has worked this dry ground," he writes. "Every decision we make carries risk of failure of ending that tradition."

Gardner's story is one of undoubtedly thousands of drought-related anecdotes from across the United States. There's plenty of misery to spread around: On Wednesday, the U.S. Department of Agriculture named 218 additional counties to its tally of natural disaster areas, raising the number of counties nationwide with drought designations to 1,584 in 32 states. And -- as millions of Americans have learned this summer -- if it's not the drought that's problematic, it's the drought's ugly cousin: the heat wave. More

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Restoring Mangroves May Prove Cheap Way to Cool Climate

Restoring Mangroves May Prove Cheap Way to Cool Climate.

Found along the edges of much of the world's tropical coastlines, mangroves are absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at an impressive rate. Protecting them, a recent study says, could yield climate benefits, biodiversity conservation and protection for local economies for a nominal cost -- between $4 and $10 per ton of CO2.

Mangrove forests are ecosystems that lie at the confluence of freshwater rivers and salty seas. While they make up only 0.7 percent of the world's forests, they have the potential to store about 2.5 times as much CO2 as humans produce globally each year.

These environments, along with other forms of coastal ecosystems such as tidal marshes and sea grasses, have been given the name "blue carbon" to differentiate them from the "green" carbon of other forests, where carbon is absorbed above ground in trees.

Juha Siikamäki, a fellow at the environmental economic think tank Resources for the Future and lead author of the study, says efforts to maintain mangroves could add an enormous potential for carbon offset projects. First, their importance must be publicized. More

Found along the edges of much of the world's tropical coastlines, mangroves are absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at an impressive rate. Protecting them, a recent study says, could yield climate benefits, biodiversity conservation and protection for local economies for a nominal cost -- between $4 and $10 per ton of CO2.

Mangrove forests are ecosystems that lie at the confluence of freshwater rivers and salty seas. While they make up only 0.7 percent of the world's forests, they have the potential to store about 2.5 times as much CO2 as humans produce globally each year.

These environments, along with other forms of coastal ecosystems such as tidal marshes and sea grasses, have been given the name "blue carbon" to differentiate them from the "green" carbon of other forests, where carbon is absorbed above ground in trees.

Juha Siikamäki, a fellow at the environmental economic think tank Resources for the Future and lead author of the study, says efforts to maintain mangroves could add an enormous potential for carbon offset projects. First, their importance must be publicized. More

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)